After almost ten years as a social worker in mental health and homeless services, I have developed some rather sophisticated methods of self-care. I often indulge in luxurious bubble baths. Sometimes I even wear a strand of pearls to the tub. Of course, they are fake pearls because I am but a humble social worker. Even so, this makes me feel elegant which is just what I need after talking to clients about bedbugs and bowels all day.

My most effective method of self-care is visualization exercises. I once worked on the 9th floor of a building and always imagined that the interactions from my day could not ride the elevator down past the 5th floor. And after an upsetting or otherwise disturbing work day, I visualize Harry Potter’s Professor Snape placing his wand on my temple for a Memory Extraction Spell. The grey substance of my vicarious trauma then withers out of my brain and vanishes, at least for the evening.

It occurred to me that if the fictional wizard Professor Snape is such a powerful factor in my emotional well-being, we social workers may be able to learn other lessons from more of literature’s greatest stories.

Take Tyler Durden, for example. In Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club, Tyler Durden is the split personality of an unnamed Narrator who aches to break out of his confined world. Tyler Durden is a figment, the product of the Narrator’s Dissociative Identity Disorder. The Narrator is an insipid middle-class worker with a dead-end job who suffers from depression while Tyler Durden is charismatic, anarchic and attractively dangerous.

Burnout among social workers would decrease dramatically if we disassociated our professional presence from our personal lives in the same way that the Narrator disassociates his everyday existence from that of the fervent Tyler Durden.

As social workers, we often work with clients who yearn for a time “when everything was beautiful and nothing hurt…” as Kurt Vonnegut describes in Slaughterhouse-Five. In his influential novel, Vonnegut weaves together the tale of Billy Pilgrim, a man who is unstuck in time after he is abducted by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore.

It is unclear whether Billy has been visited by aliens or he has imagined them, but Billy’s belief in this reality provides the framework for how he views the world. As social workers, it is often difficult to determine how much of what we hear is factual. We must remember that our judgements around the accuracy of a client’s account do not matter. The only thing that matters is the perspective of the individuals who are brave enough to share their tales of alien abduction with us.

Slaughterhouse-Five follows Billy through every phase of his life, concentrating on his experience as a prisoner during WWII. Vonnegut uses these distressing experiences to remind us to “accept that things happen. It may not be for a reason, and you may have no control over it, but the first step to getting through it is accepting what it is.”

As social workers, we impart this wisdom onto our clients. We support and embrace the individuals we serve as they seek to accept whatever tragic, unsettling and otherwise unfortunate things have happened to them.

We must also remember this wisdom for ourselves. We often perceive that we have more control than we do and personalize the choices made by others. Instead we social workers can accept that things happen. We can accept that our clients may overdose, relapse, abandon their apartments, kill themselves, spend all their money, mismanage their physical conditions, or disappear without a trace. We can admit we have no control and accept things for what they are rather than what we wish them to be.

And while accepting that things happen, we must also never stop advocating for our vulnerable clients as Randle Patrick McMurphy’s in Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. To avoid prison following a dishonorable military discharge for insubordination, this story’s hero has himself declared insane. McMurphy ends up in a mental institution run by a tyrannical nurse and seeks to unshackle the other patients from the cruel oppression. Throughout the story, McMurphy teaches the ward’s patients to stand up for themselves and enjoy life despite their circumstances.

We social workers also seek to unshackle our clients from whatever form of oppression with which they are saddled but we cannot forget that despite dire circumstances, every human deserves to have fun, to feel pleasure and joy, and to laugh. Social workers should also be cautious about over functioning for individuals rather than empowering them to stand up for themselves against repressive and unfair forces.

In the His Dark Materials trilogy, Philip Pullman said, “Life is brutal and will break your heart, and you just have to be brave and do the best you can.”

To my fellow social workers I say social work is brutal and will break your heart. It will crush your spirit. It will chew you up but it will not spit you out. It will swallow you instead. You just must be brave and do the best you can.

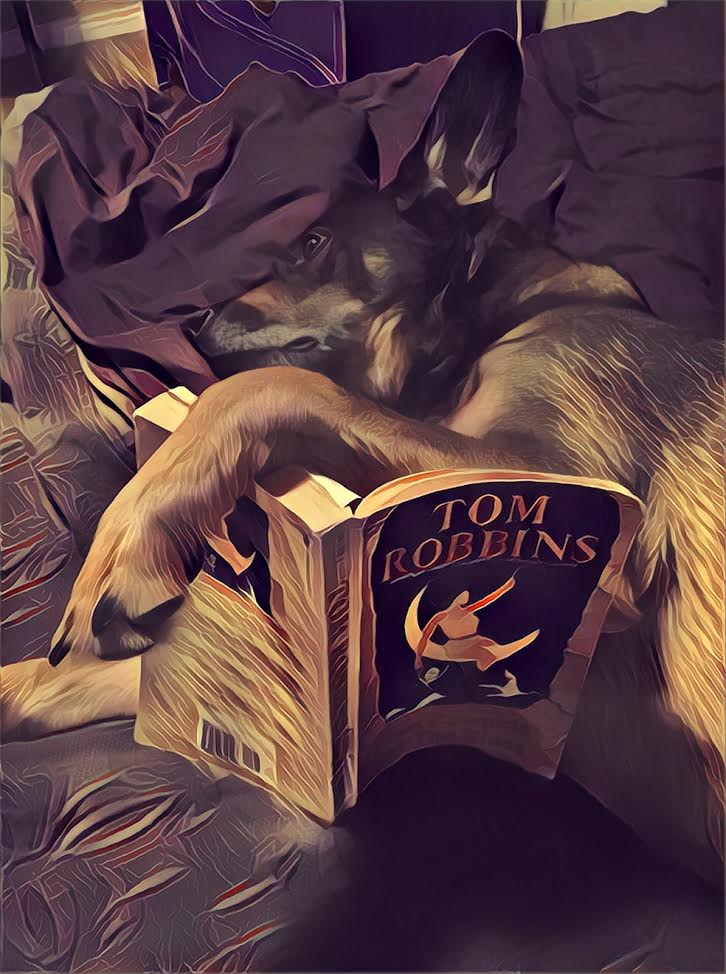

And when all else fails, grab a book. You just might learn a valuable social work lesson or two.